I drew along with my life drawing students because I believed it was the way to best illustrate my teaching theory to them. It also kept me in touch with my work process. For example, if I started a sketch by determining which leg bore the primary weight of a specific pose, I was reminded to mention the importance of that observation to my students.

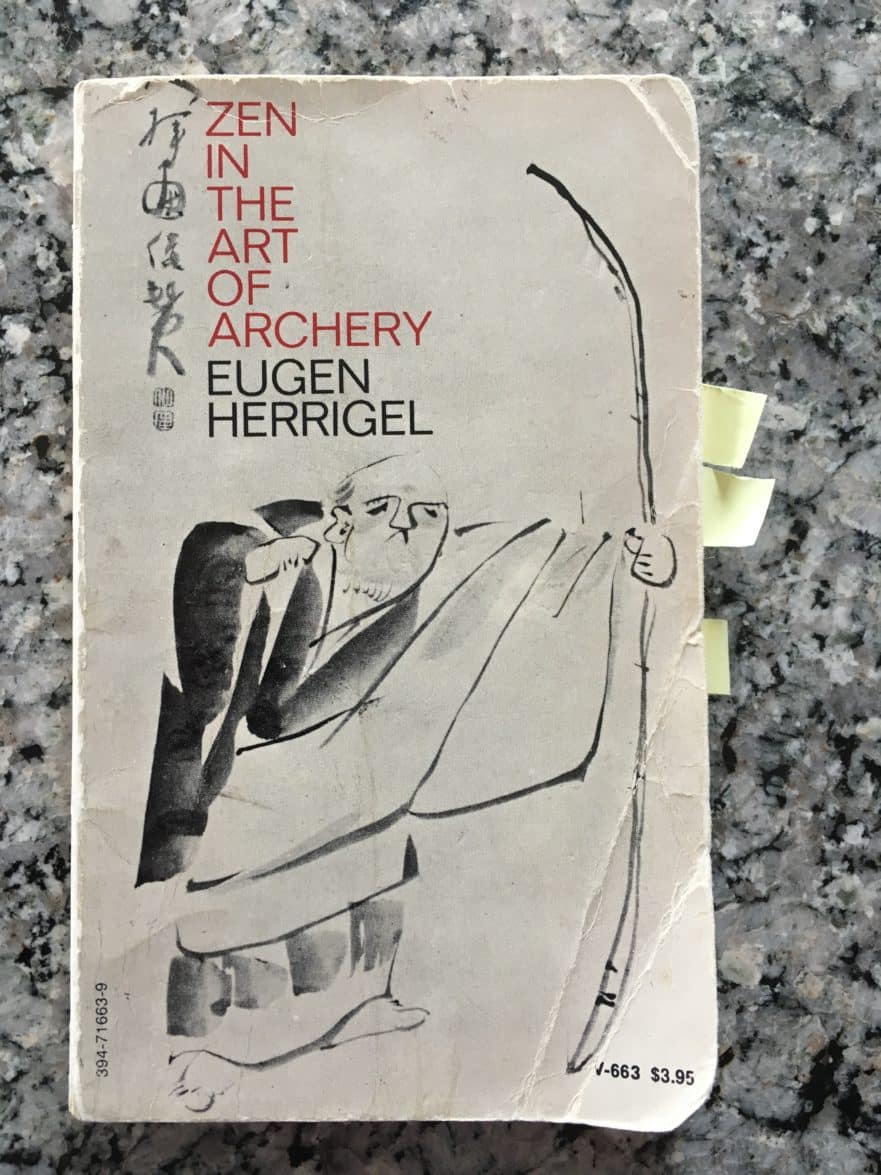

In preparation for our study, the students and I read Zen in the Art of Archery by Eugen Herrigel. The text acted as a metaphor for our learning journey. In that book, my students were exposed to the trials and tribulations of a German philosopher attempting to study Zen Buddhism through the practice of ancient Japanese archery. The philosopher’s journey was arduous and when he lost faith, the Zen master was more likely to mount a simple demonstration illustrating his devotion to the practice of archery, than to speak.

Many students told me that reading the beloved book had enabled them to keep faith in the life drawing learning process at those times they felt similar frustration. They also said that they benefited from having me draw with them, and one – Allison Watts – expressed with great eloquence her awareness of the connection between the text and my teaching by example. Here is what she wrote:

“When we were told on the first day that we would be required to stand the whole three hours of class, I groaned with everyone else… Little did I realize the importance of standing until after I was done reading our text, and I came to class actually eager to be on my feet, anticipating the moment when my whole body would become part of the picture on my page. I understood by then, my goal was not making the best picture, but making the picture that had the most of me in it.

I watched, almost jealous, at the first demonstration of the day, searching more our master for the answers, not the art she produced. I watched as, with eyes closed, a person appeared under her hand, full of all the life its creator had given it – not just with her hand, but with her whole body, heart, and soul. It was as if the figure on the page was a testimony of the energy within our master, not of our master’s skill with charcoal, and somehow she had transferred her energy to the charcoal, adapting it as an extension of herself, as was the page she used.”